I’ve been thinking about writing this post for quite some time. The concepts and thoughts presented here have been on my mind since I re-entered the workforce in a traditional sense over a year ago. I’ve alluded to some of my thoughts on Twitter, but decided it was time to put something in long form.

The thing that finally put me over the top was an article sent to me by my good friend and colleague, Mark Neuenschwander. Mark and I have been going back and forth for a long while on the pros and cons of self-driving cars. I’m all for it. He’s a bit more cautious with the concept. The article Mark sent – Crash: how computers are setting us up for disaster – contains a short paragraph supporting one of his main objections, mainly that humans may not be ready for self-driving vehicles.

With that said, the article goes way beyond a paragraph or two about self-driving cars. The author of the piece presents great insight into how humans are losing the ability to think and act for themselves as a result of automation. This is something the author refers to as the paradox of automation.

This problem has a name: the paradox of automation. It applies in a wide variety of contexts, from the operators of nuclear power stations to the crew of cruise ships, from the simple fact that we can no longer remember phone numbers because we have them all stored in our mobile phones, to the way we now struggle with mental arithmetic because we are surrounded by electronic calculators. The better the automatic systems, the more out-of-practice human operators will be, and the more extreme the situations they will have to face. The psychologist James Reason, author of Human Error, wrote: “Manual control is a highly skilled activity, and skills need to be practiced continuously in order to maintain them. Yet an automatic control system that fails only rarely denies operators the opportunity for practicing these basic control skills … when manual takeover is necessary something has usually gone wrong; this means that operators need to be more rather than less skilled in order to cope with these atypical conditions.”(1) –emphasis is mine

At this point, you’re probably wondering what this has to do with pharmacy. I’m getting to that.

I’ve been a pharmacist for the past 20 years, but have only been involved on the periphery for the past ten. I was an IT pharmacist from 2007 to 2010, a product manager at Talyst from 2010 to 2013, and an independent pharmacist consultant from 2013 to 2016. Recently I re-entered the pharmacy workforce as a staff pharmacist. Besides realizing that the day-to-day operations of an acute care pharmacy are basically unchanged, I noticed that new pharmacists – those that are fresh out of school with less than two or three years of acute care experience – are risk averse, lack creativity, don’t think outside the box, and lack the willingness to make expert judgment calls. In a nutshell, they are missing the very qualities necessary to qualify them as professionals in the healthcare field.

Pharmacists are relied upon, and paid well, to make tough decision, take on risk and responsibility, and come up with creative solutions to difficult medication-related problems. A trained monkey can perform most pharmacist-related work tasks when things are going exactly as planned.(2) It is only when things get complicated that pharmacists are there to apply a unique skillset to the problem. Unfortunately, I have witnessed a decline in the ability of new pharmacists to apply these skills to complex situations.

The cause of this decline is a bit of a mystery to me. I’ve speculated often as to the cause. It’s certainly not for a lack of intelligence. The new pharmacists I have met over the past year are certainly bright enough. It’s not the schools, or at least I hope it’s not the schools. The curriculum’s I’ve seen are more than adequate. Is it a lack of experience? I’m sure that plays a part, but it doesn’t explain the lackluster willingness to problem solve. Could it be my age? I mean, every pharmacist I’ve ever met thinks their generation did it better than the current generation. Maybe there’s a little bit of truth to that, but I don’t think that explains everything I’ve seen. No, it’s something else.

It wasn’t until I read the Guardian article cited above that things started to come together in my mind. It’s clear that the paradox of automation is playing a role. Better systems and more technology have led to fewer opportunities to practice basic skills that are necessary for pharmacists to perform at a high level. Smartphones and computer software have taken the place of a pencil and calculator. Strict protocol-driven care has taken the place of common sense and logic. But that doesn’t explain everything, especially when you consider how unautomated pharmacies are. It’s no exaggeration when I say that pharmacy practice is at least ten years behind in the technology race. No, the problem cannot be blamed entirely on the paradox of automation. There’s more to it. Something more insidious. Something hidden in plain sight, but unseen. And that is the ever increasing number of pharmacy regulations and the proliferation of complex policies and procedures heaped on pharmacy practice.

Our overreliance on data and algorithms is eroding away at pharmacist’s ability to judge things for themselves and depriving them of decision-making opportunities.

Gary Klein, a psychologist who specializes [sic] in the study of expert and intuitive decision-making, summarises [sic] the problem: “When the algorithms are making the decisions, people often stop working to get better. The algorithms can make it hard to diagnose reasons for failures. As people become more dependent on algorithms, their judgment may erode, making them depend even more on the algorithms. That process sets up a vicious cycle. People get passive and less vigilant when algorithms make the decisions.” – emphasis is mine

This is what is happening to pharmacists. New grads, or those with limited practical experience, are relying too much on policies and procedures as a way to skirt tough decision. Instead of thinking logically about the problem and applying their deep understanding of pharmaceutical care, they are hiding behind page after page of arbitrary guidelines, sometimes to the detriment of the patient. In a sense, pharmacists have stopped working to get better and their judgment is fading.

There are times during the care of a patient when the right answer may not be written into a policy. In a worst-case scenario, the right thing to do for the patient may go against what’s written in the policy. During those times, a pharmacist in cooperation with other healthcare providers need to work together to make decisions based on expert judgment and experience. Sometimes these decisions can be tough and often times fall outside “the norm”. I’ve been involved in a few tough calls during my 20 years, and none of them were simple black-and-white matters.

Pharmacists practicing today cannot shy away from tough decisions. They can’t pass the buck. They can’t point to rules and regulations as a reason not to do something that they know should be done.(3) What I’ve observed is a serious problem. It threatens the credibility and the future of pharmacists as medication experts. When a pharmacist can’t think outside the box and apply their skills to complex problems in unique ways, they become no better than a reference book.

Think about it.

——

- If you’ve been in healthcare for any amount of time, you will recognize the name James Reason. He’s basically the father of the “Swiss Cheese model” of how errors occur. Every patient safety expert I’ve ever met uses the Swiss Cheese model to explain how errors occur in hospitals.

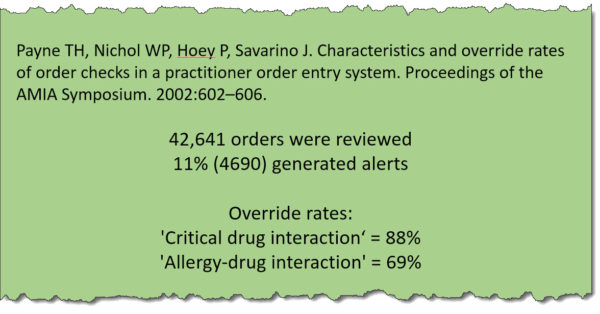

- My thoughts on this are well documented throughout my website. I stand by my opinion that a majority of what a pharmacist does on a routine basis requires no specialized knowledge or skill. See this video for a pharmacist verifying orders in an EHR/CPOE system.

- I’m not saying there isn’t a place for rules, because there is. I’m saying that regulatory requirements and policies cannot cover every scenario. It’s not possible. There will be times when the best, most thoughtful policy won’t cover what’s happening to a patient.